The goal of this work is to identify which provisioning factors affect the relationship between energy use and need satisfaction, as well as to assess which factors are relatively the most significant.

To do this, I build on the basic model and the concept of provisioning factors in Vogel, 2021 [^1]. I apply concepts from social ecology and ecological economics to break down the process of provisioning into distinct stages, and to pin down the factors involved at each stage.

I then identify specific quantiative and qualitative indicators for each factor that can be used in statistical models to understand how different provisioning factors contribute to the provisioning systems and affect the energy use/need satisfaction relationship.

Provisioning Process ("the Flow")

I look at provisioning systems through the lens of Georgescu-Roegen's flow-fund model, using the idea of resource flows as developed in the field of social ecology. Stocks, such as energy or material resources, as well as funds, such as labor, land and capital, are first extracted/activated as part of provisioning, and then transformed, moving through the provisioning process as flows within the context of a given society, to deliver use value and then be dissipated as waste.

I add accumulation of stocks (e.g. capital) as another, distinct endpoint of the transformation process, on par with need satisfaction and dissipation as waste, following the concept of "appropriating systems" in Fanning, et al., 2020 [^2]. I don't make the specific distinction between appropriating and provisioning systems within the provisioning process to avoid unnecessary complexity, but rather consider that resources and energy going into (capital) stock accumulation are "taken away" from other goals, such as immediate need satisfaction.

I define need satisfaction broadly, as in Vogel, 2021, to include measures such as sufficient nourishment, access to water, sanitation, as well as education, life expectancy, life satisfaction, etc.

The provisioning process that consists of extraction, transformation and dissipation stages, is moderated by decision-making structures present in a given society, which is a catch-all term for everything that is not directly part of provisioning process, but influences it by affecting decisions made within the system, through mechanisms such as politics, culture, income and other inequalities, etc.

The basic model is illustrated by the "provisioning flow" diagram below:

- Provisioning flow diagram

In the previous version of the same process, part of transformed energy and resources would return to original stocks and funds, e.g. adding to capital via accumulation or contributing to labor base via education. I don't use this anymore as this does not align with frameworks used in social ecology literature and does not sufficiently capture the fact that transformed resources cannot be returned back to their original state, as pointed out by Georgescu-Roegen.

Provisioning Factors and Indicators

In the provisioning flow model, provisioning factors are defined as a) properties of one of the stages of the provisioning process, such as extraction, transformation, or dissipation); or b) properties of the decision-making process by which a society governs its provisioning. This distinction allows me to look at provisioning factors involved in each process in more detail; e.g. I would look at the energy systems of a given society in the context of the extraction process, and can analyse waste recycling systems in the context of dissipation.

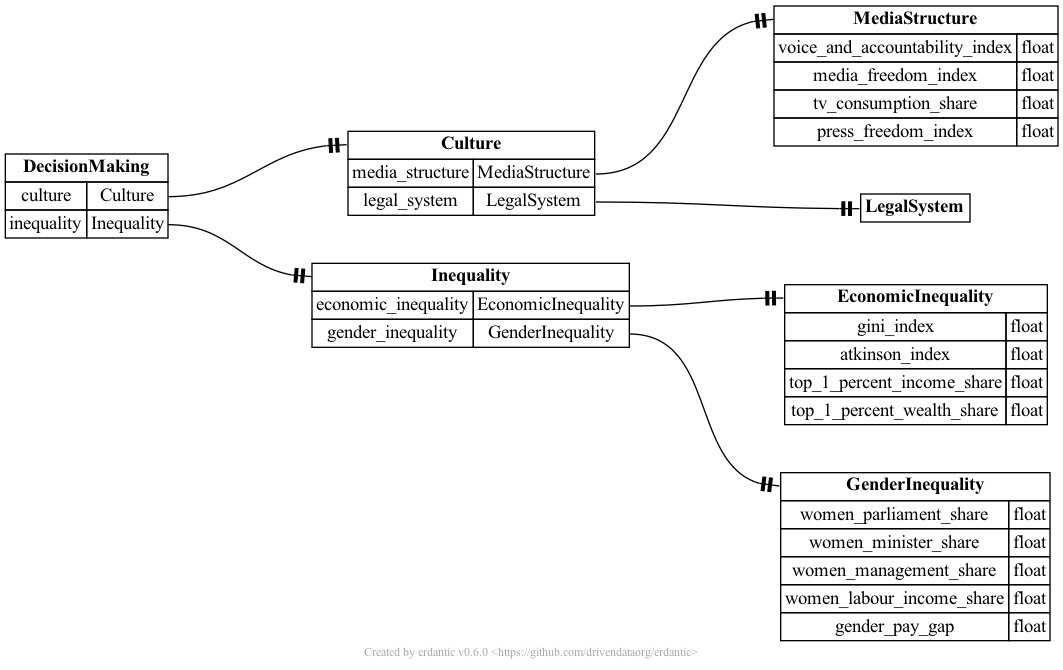

Each provisioning factor can be described by one or more indicators that are either quantitative measures, defined as numeric variables, or qualitative indicators, defined as categorical or binary variables, that describe the provisioning factor. For example, an "economic inequality" provisioning factor can be described by a "Gini index" indicator, but can be also explained by any number of other indicators that are either qualitative , or quantitative, such as the Atkinson index, top 1% income share, characteristics of wealth distribution, etc.

-

Example of provisioning factors ("EconomicInequality", "GenderInequality"), and their respective indicators (e.g. "gini_index", "women_minister_share")

To better understand the structure of the transformation process, I use the concept of the "foundational economy" [^3][^4], which allows to separate activities in the provisioning system into household work that's left out of the monetary economy but required for the system to function ("core economy"), activities critical for providing basic needs of the population and/or maintaining infrastructures ("foundational economy"), activities culturally defined as essential mostly provided through markets ("overlooked economy"), and everything else, including the competitive sectors, such as IT and Finance.

Another dimension of the transformation process is added by the concept of "provisioning realms" , as developed by Raworth and used in Fanning [^5], which emphasises the difference of the processes of provisioning conducted by households, market, commons and the state.

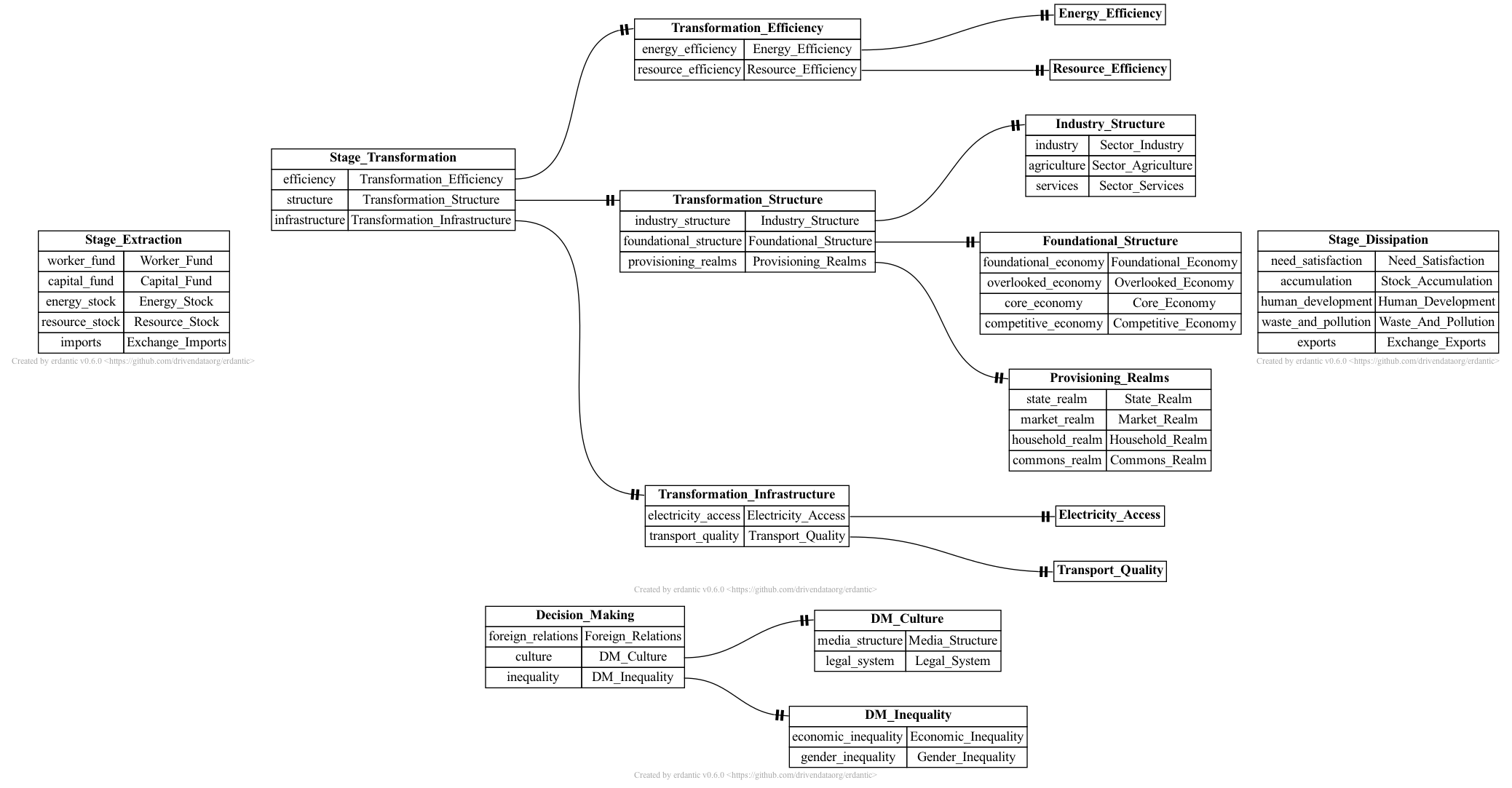

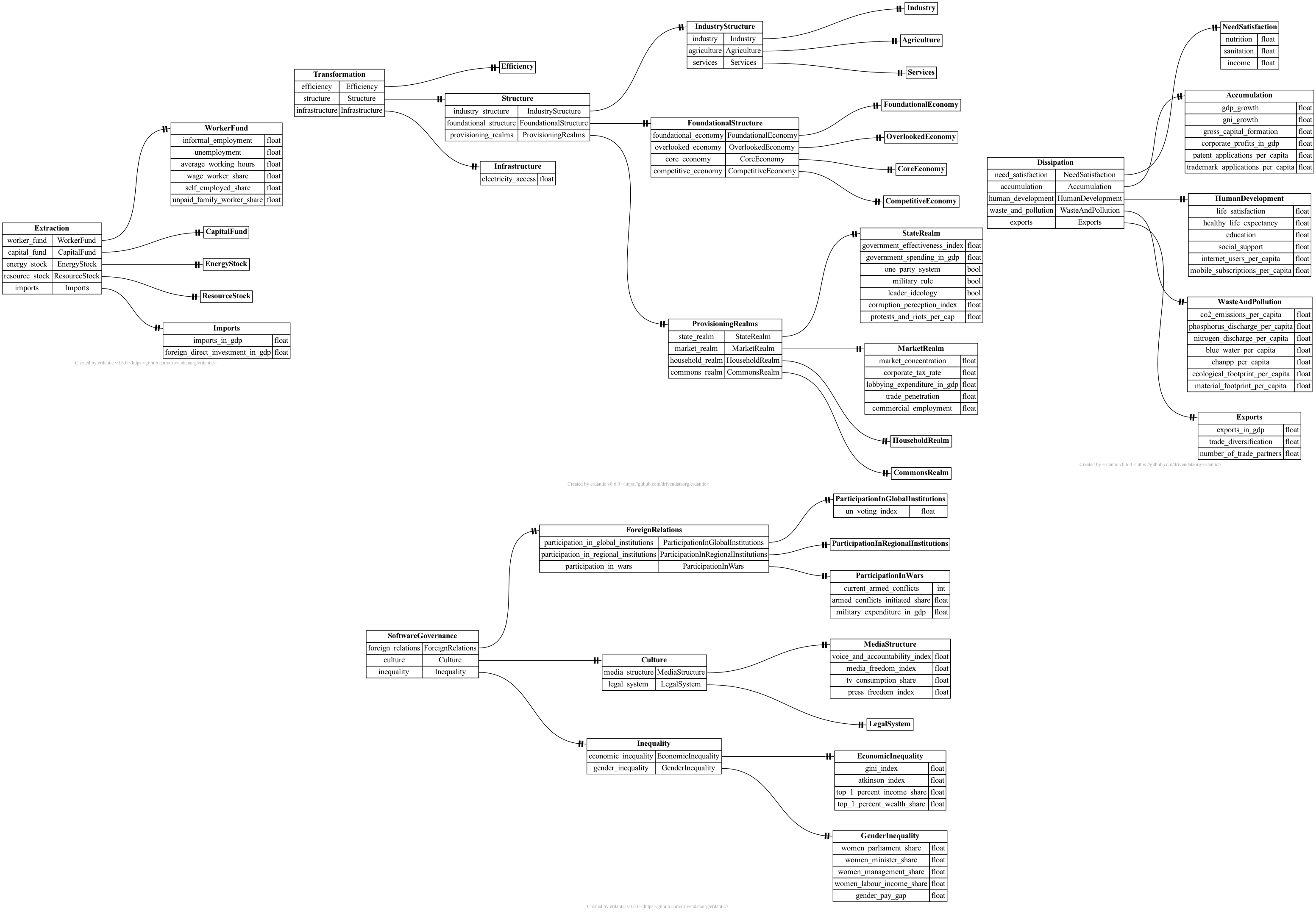

-

Provisioning flow as a domain model with objects. Each of the fields on the objects corresponds to a provisioning factor. In the detailed version, suggested quantitative/qualitative measures for each factor are shown.

-

Detailed version (Zoom in to see the provisioning indicators for each factor)

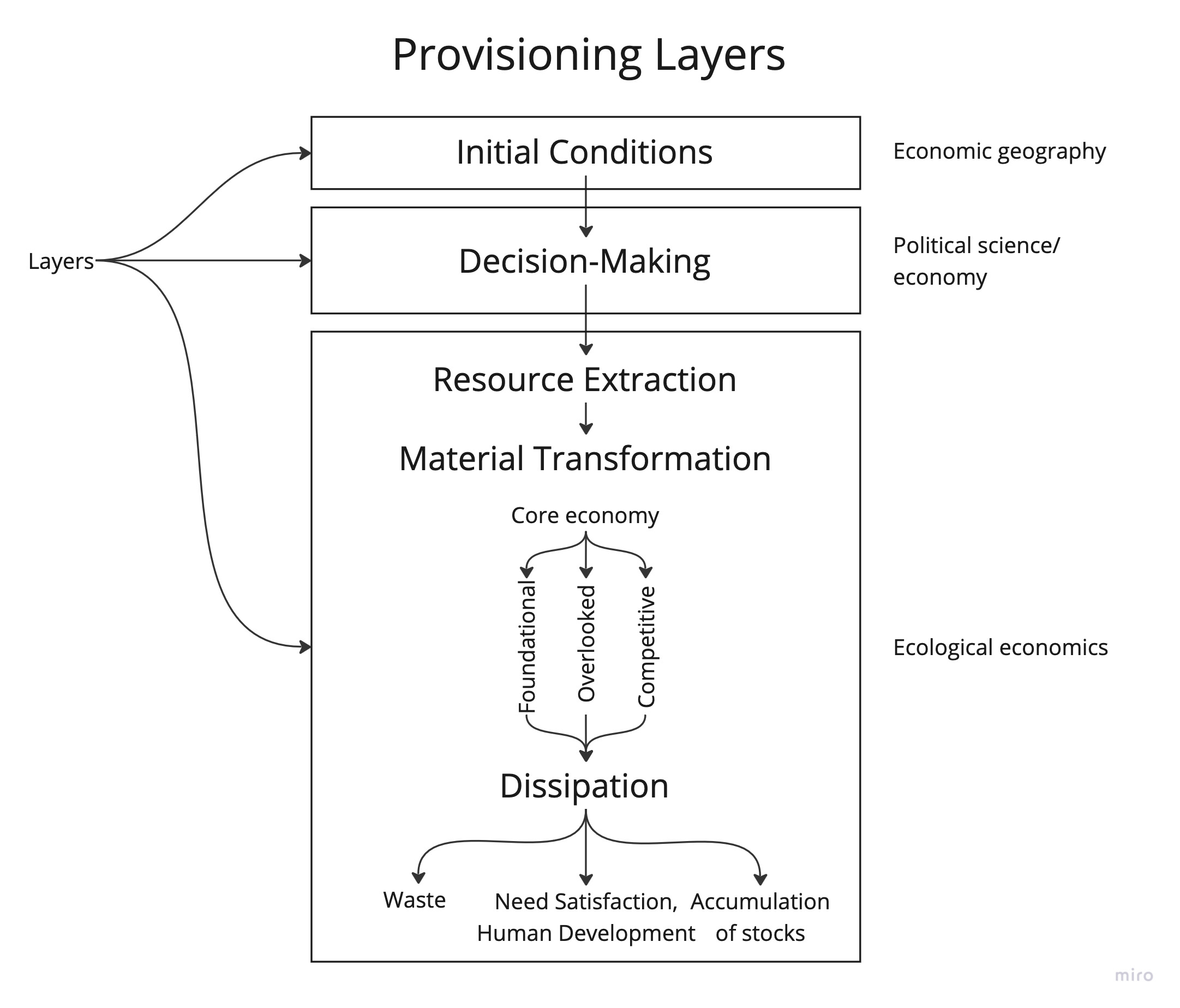

Provisioning Layers

The same model can also be understood as a set of "layers" that follow, in chronological order, the process of provisioning, from the initial conditions (the stocks available and their distribution, geographical location, the level of urbanization etc.), to how the decisions are made on what to produce and how, to the actual provisioning process.

The advantage of this is that each of the layers can be mapped to a subject area studied by a scientific discipline — e.g economic geography studies initial conditions of provisioning, political ecnomy studies decision making, and ecological economics/social ecology look at the provisioning process itself, from extracting resources and energy to dissipating the output. Respective research areas can provide clues as to which provisioning factors are involved in each of the layers, and what indicators are useful to look at to understand a given factor.

-

Additional details ("layers") and the fields that study them

Applying the Model

Looking at provisioning systems through the lens of social ecology allows to identify the provisioning factors involved at each stage of energy/resource flow, independent from the specifics of the social system (e.g. if it's a predominantly agricultural, or an industrial society).

This provides a relatively context-independent framework that at the same time can be used to narrow down individual provisioning factors with their related quantitative or qualitative indicators to describe provisioning.

Once individual factors and their indicators are known, their contribution to the relationship between energy use and need satisfaction can be analysed by means of statistical modeling or by using qualitative research approaches.

Sources

[^1] Vogel, Jefim, Julia K. Steinberger, Daniel W. O’Neill, William F. Lamb, and Jaya Krishnakumar. “Socio-Economic Conditions for Satisfying Human Needs at Low Energy Use: An International Analysis of Social Provisioning.” Global Environmental Change 69 (July 1, 2021): 102287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102287.

[^2] Fanning, Andrew L., Daniel W. O’Neill, and Milena Büchs. “Provisioning Systems for a Good Life within Planetary Boundaries.” Global Environmental Change 64 (September 1, 2020): 102135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102135.

[^3] The Foundational Economy. “What Is the Foundational Economy?,” January 15, 2017. https://foundationaleconomy.com/introduction/.

[^4] The Foundational Economy. “Activity Classification,” January 19, 2019. https://foundationaleconomy.com/activity-classification/.

[^5] Raworth, Kate. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2017.